ဘာရယ္ မဟုတ္ဘူး၊ သူငယ္ခ်င္း တစ္ေယာက္က ကိုယ္တိုင္ေရး Paper ေတြ ဘာေတြ ရွိရင္ တင္ပါလား ဆိုတာနဲ႔ တင္လိုက္တာပါ။ စာလည္းမၾကည့္ခ်င္လို႕။ ပထမ ႏွစ္တုန္းက မေရးတတ္ ေရးတတ္ နဲ႔ ပထမဆံုး ေရးထားတဲ႔ Assignment paper ပါ။ Publication ေတာ့ မဟုတ္ပါဘူး။

Prevention and Protection against Invasive Plant Species

By Pyi Soe Aung ( March 2011)

Introduction

Today, with heavy pressure of world population, it is crucial to maintain our life supporting systems. And conservation of biological diversity is the best way to achieve this, since it underpins a wide range of ecosystem services on which human societies have always depended for food and fresh water, health and recreation, and protection from natural disasters and so on (CBD, 2010). However, major alterations and loss of biodiversity are being experienced due to various reasons. One of the factors that contribute to loss of biodiversity is due to the introduction of invasive species, which could competitively suppress native species populations and alter habitats and ecosystems (Wetzel, 2005). Generally, the impacts of invasive species cost at least US$ 1.4 trillion annually – close to 5% GDP (Pimental et al., 2001; GISP, 2009) and they pose the biggest single threat to food security and human health. Also the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment had classified invasive species along with climate change as the two drivers damaging ecosystem function and human well-being that are the most difficult to reverse (Hassan et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2008). In this regard, it has become crucial important to prevent, protect or ameliorate the introduction of those alien species as well as their impacts towards ecosystem, habitats and species diversity. Early warning system, eradication and control as well as increased awareness and political leadership have become necessarily to be implemented. Also, global, regional and bilateral efforts including standards and guidelines, monitoring and assessment has come to be essential.

Since invasive plant species have a significant effect on the biological and human communities in which they appear, their appearance in both terrestrial and aquatic landscapes is associated with human activities and technology development that affect the environment. Various studies had highlighted that invasive plant species are increasing due to increased global movement of people, trade and transport of biological and agricultural commodities and unusual plant materials (Dekker, 2005). Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the means and routes by which invasive plant species are imported and introduced into new environments. Also various authors had highlighted that prevention or protection of these routes or pathways could be the best way to mitigate or ameliorate the harmful effects by these species (NISC, 2001; Clout and Williams, 2009). However, in reality, application of prevention and protection measures to these pathways or entries of invasive species had experienced various difficulties to achieve, particularly due to the absence of physical or ecological barriers to their movement (Clout and Williams, 2009). Therefore, it is necessary to consider effective management and control of these species other than protection alone, based on their nature and impact behavior to native species and environment.

Historical concerns on invasive species

Various authors and international organization had defined invasive species in different ways (Wittenberg et al., 2001; Inderjit et al., 2005; ISAC, 2006; NISC, 2008). Generally, an invasive species can generally be defined as “an alien species whose introduction does or is likely to cause economic or environmental harm or harm to human health (ISAC, 2006; NISC, 2008).” This definition relates to many types of invasive species such as plants, animals and microorganisms and focuses upon invasive species which are harmful, rather than focusing on non-native species, most of which are not harmful. However, in this case, as highlighted by Invasive Species Advisory Committee (ISAC), plant and animal species under domestication or cultivation and under human control are not invasive species (NISC, 2008). Also according to Global Invasive Species Program (GISP) founded by CABI, IUCN and TNC, invasive alien species are defined as non-native species that threaten, or have the potential to threaten, the environment, health or economic production

The history of plant invasion started since the time of early human immigrants, in which people not only brought language and culture with them, but also plants and animals that are familiar and useful to their cultures (Inderjit et al., 2005). Historically, concerns over the potential impacts of invasive species began in the late 18th century, notably John Bartram, an 18th century botanist, who noticed that some introduced plants negatively affected the environment and some were extremely difficult to control (Mack RN, 2003; Inderjit et al., 2005). For many decades, since the era of Charles Darwin (1809-1882) through Charles Elton (1900-1991), scientists had explicitly been studying to understand the process and dynamics of invasions and also trying to develop theories and approaches in order to predict and prevent invasion by harmful invasive plant species (Inderjit et al., 2005). And also various international conventions and organizations, such as CBD, IUCN, NISC, GISP, had also been trying to propose legal instruments and frameworks so as to support and underpin practical management and protection of these species. However, up to present days, invasive species are still invading and threatening to our biodiversity and human life supporting systems (Clout and Williams, 2009).

Conceptual process of invasion

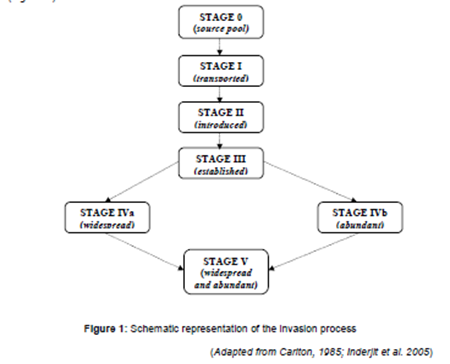

The process of invasion, according to the stage-based approach by Carlton J. (1985), can be analyzed through a framework with a series of consecutive stages (Carlton, 1985; Inderjit et al., 2005). This framework begins with transport and introduction stages, passing through the establishment of self-reproducing populations, and ending with the spread and abundance (Figure: 1).

In the figure, Stage 0 represents species or population resident in a source region. Invasion process starts in Stage I where species or population could be found in a transport vector. After that Stage II identified as introduced to a new region, but not establishing self-reproducing populations. And then formation of a self-sustaining population occurs in Stage III. In the case of stage IV it can be divided into two: stage IVa which represents several independently established populations (widespread), which undergoes long distance introduction or subsequent local spread, but remaining low in density; and Stage IVb in which a small number of populations, but with a high density of individuals occur (abundant). Finally multiple populations that are generally high in density are established in Stage V (Carlton, 1985; Inderjit et al,. 2005). Basically, each stage undergoes a sub-sampling of individuals, such as widespread and abundant – many invaders are introduced, but few established, and however even fewer could become widespread or abundant in new environment (Inderjit et al., 2005).

Pathways of invasion

In order to prevent and mitigate the harmful effects of plant invasive species, it is essential to understand the ways and routes by which invasive plant species are imported and introduced into new environments. According to Maynard and Nowell (2009), pathways of plant introduction into the new areas can be differentiated into three broad categories: 1) natural introduction, 2) accidental introductions and 3) deliberate introduction;

Natural introduction or host range extension

Invasive species can naturally spread either actively through flying, crawling or swimming, or passively by water, animals or wind (Clout and Williams, 2009). In some cases, human modification of the environment may result extension of their host range to wider areas. Moreover, natural disasters such as cyclones can result in the movement of organisms over abnormally long distances, and also large-scale disturbance of landscapes can create conditions in which invasive organisms can easily establish (Clout and Williams, 2009).

Accidental introductions

Invasive species can also be accidentally introduced through hitch-hiking or vectored on/by something such as; during trade; movement of material during emergency relief or conflicts; traditional movement of people; movement of plants, animals, or soil; scientific materials; traveler’s personal effects; ships, including ballast water etc. (Clout and Williams, 2009). Most of these accidental introductions, as highlighted by Maynard and Norwell (2009), normally enter via contaminants of commodities or organisms, or due to the movement of people from one continent to another.

Deliberate introductions

Invasive species can also be deliberately introduced in many ways including pasture and genotype improvement, new crops, biological control, land rehabilitation as well as leisure activities (Clout and Williams, 2009). These may be introduced legally or illegally into an area and can have wide reaching, and often unexpected consequences. However, in some cases, a further layer of complexity normally arises when one community considers an organism invasive and another community considers the species beneficial (Maynard and Nowell, 2009).

Protection and management of invasive plant species

In order to achieve protection and management of these invasive plant species, several strategies and action plans has been developed from different government and non-government organizations (Wittenberg et al., 2001; NISC, 2001; ; Inderjit et al., 2005; ISAC, 2006; Clout and Williams, 2009). However, the basic principles for effective protection and management of invasive plant species can be categorized into three major concepts;

- Prevention of the entry of potential species into the new area (pre-entry),

- Early detection and rapid response through reducing and eliminating the likelihood that the species will become established or spread and decreasing or eliminating the presence of invader, and

- Management and control by providing adaptation measures through changes in behavior in order to reduce the impacts

Prevention

Prevention is the first and most cost-effective measure against invasive alien species since an introduced species has once become established in an area, it can be extremely difficult or more often impossible to eradicate (NISC, 2001). In order to achieve prevention against invasion, the most effective tool is a risk analysis and screening system for evaluating early intentional introductions of non-native species, before any entry is allowed to the new habitat (Clout and Williams, 2009).

Risk assessment of invasive species

Risk assessment processes are commonly used to rate and rank the species those are suspected to be invasive (NISC, 2001; Wittenberg et al., 2001). The objectives includes to predict whether or not a species is likely to be invasive and a relative ranking of risks so as to achieve guidance for prevention and screening efforts; for planning of an early detection and rapid response programme, and for selecting priority species and priority areas to establish control and restoration (Stohlgren and Jarnevich, 2009). Based on the guidelines prescribed by Global Invasive Species Programmes (GISP), the risk assessment process should begin with the identification of candidate species and pathways, through the review of scientific and other literature together with expert opinions and qualitative and quantitative analysis, resulting in priority ranking of their relative risks (Wittenberg et al., 2001).

According to Stohlgren and Jarnevich (2009), the general strategy for risk assessment of invasive plant species could be summarized as follows;

- Classification of potentially harmful species traits

- Matching those traits to suitable habitats

- Estimating exposure including detailed information on population and viability of the organisms, and the habitat susceptibility to invasion

- Surveys of current distribution and abundance

- Estimation of the potential distribution and abundance, and potential rate of spread

- Assessment of probable environmental, economic and social impacts

- Selecting priority species to control, based on the relative risks, legal mandates, country regulations, and a sense of urgency based on their social considerations

Exclusion

The most effective method of preventing unintentional introduction of non-native species is to identify the pathways by which they are introduced and to develop environmentally sound methods to interdict introductions (NISC, 2001). Also Maynard and Nowell (2009) highlighted that control of pathways of entry of known invasive organisms through quarantine system provides the best opportunity to prevent the entry. In this case, Wittenberg et al. (2001) had outlined three major processes of quarantine systems in order to stop further invasions;

- Interception of the entry of invasive species based on regulations and enforcement which may be before exportation or upon arrival of goods and trade. This may include quarantine laws and regulations, risk assessment database, high inspection capacity as well as public education;

- Treatment of goods and packaging material that are suspected to be contaminated with non-indigenous organisms. This may include biocide applications (e.g. fumigation, pesticide application), water immersion, heat and cold treatment, pressure or irradiation;

- Prohibition of trade based on international regulations when even strict measures will not prevent introductions through high-risk pathways. This can be applied with respect to particular products, source regions, or routes;

Early detection and rapid response

Since even the best prevention efforts cannot stop all introductions, early detection of initial invasions and quick coordinated responses are needed to eradicate or control invasive species before they become too widespread and control becomes technically and financially impossible (NISC, 2001). Basically, early detection, as defined by Worrall (2002), is a comprehensive, integrated system of active or passive surveillance to find and verify the identity of new invasive species as early after entry as possible. And also early detection systems should be targeted at the areas where introductions are likely, such as near pathways of introduction, and sensitive ecosystems where impacts are likely to be great or invasion is likely to be rapid (Worrall, 2002).

However, once the identity of new invasive species is detected through early detection, it should be rapidly responded to control or eradicate this species from the region. According to Worrall (2002), rapid response should be a systematic effort to eradicate, contain or control invasive species while the infestation is still localized, and it may be implemented in response to new introductions or isolated infestations of a previously established, non-native organism. Also, preliminary assessment and subsequent monitoring should be provided as part of the response so that the response is rapid and efficient (Worrall, 2002).

Basic components or key elements for early detection and rapid response programme, according to NISC (2001), include: 1) access to current and reliable scientific and management information; 2) ability to identify species quickly; 3) standard procedures or a functional risk assessment plan; 4) mechanisms in place to coordinate a control effort; and 5) providing adequate technical assistance (e.g. quarantine, monitoring, information sharing, research and development, and technology transfer) and 6) rapid access to stable funding for accelerated research of invasive species biology, survey methods, and eradication options (NISC, 2001; Holcombe and Stohlgren, 2009). Each of these elements, particularly points 1 and 2 are important for effective early detection and rapid response programme.

Another important tool that can aid in those specific processes is establishment of ‘watch lists’ (NISC, 2001), which, as defined by Holcombe and Stohlgren (2009), are lists of species that are either nearby, or known to invade similar habitats to the area of the list. However, this requires a global scale information exchange system which share data and information from all over the world (Holcombe and Stohlgren, 2009). Therefore, once information about a particular invasive species in a local area is obtained, it should be shared on global websites and with local land managers so that others can benefit from this knowledge.

Management and control

When invasive species appear to be permanently established, the most effective action may be to control and manage their spread or reduce their impacts through providing control measures (NISC, 2001). Generally, three main strategies (NISC, 2001; Wittenberg et al., 2001; Grice, 2009) had outlined for dealing with management and control of these established invasive alien species: eradication, containment and control, and mitigation.

Eradication

When prevention has failed to stop the introduction of an alien species, eradication programmes should be taken into action (Wittenberg et al., 2001). Basically, eradication means the elimination of the entire population of an alien species, including any resting stages, in the managed area (NISC, 2001). However, eradication is possible only prior to naturalization, during the earliest part of the expansion stage, or isolated populations (Cacho, 2004; Mack and Foster, 2004; Mc.Neeley et al., 2005; Grice, 2009). And also, the method of eradication depends on the type of invasive species. Successful eradication methods, as summarized by NISC (2001), include: 1) cultural practices (e.g., crop rotation, re-vegetation, grazing, and water level manipulation); 2) physical restraints (e.g., fences, equipment sanitation, and electric dispersal barriers); 3) removal from the area (e.g., hand-removal, mechanical harvesting, cultivation, burning, and mowing); 4) the judicious use of chemical and bio-pesticides; 5) release of selective biological control agents (such as host-specific predator/herbivore organisms); and 6) interference with reproduction (e.g., pheromone-baited traps and release of sterile males) (NISC, 2001).

Containment and control

When eradication of an invasive organism becomes impractical, the strategic options are containment and control. Basically, containment can be defined as the restrictions to an invasive species’ distribution, whereas control is the management that attempts to reduce the impact of an invasive species without necessarily restricting its range (Grice, 2009). In general, containment may be the most appropriate strategy for a species during the early expansion stage, whereas a control strategy is likely to be most suitable for an advanced stage with a large and extensive population (Wittenberg et al., 2001). Moreover, an important component of a containment program, as described by Wittenberg et al., (2001), is the ability to rapidly detect new infestations of the invasive species both spreading from the margins of its distribution, or in completely new areas, so that control measures can be implemented in as timely a manner as possible.

However, in some cases where neither eradication nor containment of an invasive species is possible, the only option, as recommended by NISC (2001), is whether to control or to do nothing. And also the decisions on whether to attempt control or not, will generally depend on: 1) the importance of the impacts that the invasive species has, relative to its estimated costs for control; 2) the stage to which the invasion has progressed; and 3) the availability of control measures (Grice, 2009). Specifically, it is necessary to apply, as recommended by Wittenberg et al, (2001), mechanical, chemical and biological control, together with habitat and ecosystem management methods so as to achieve successful control of invasive species especially in population levels. According to the research taken by Grice (2009), some successful examples of invasive plant control was recorded through the use of the following methods: 1) manual methods (e.g. hand-pulling, cutting, mowing, bulldozing, girdling); 2) the use of herbicides, including release of biological control agents; 3) controlled use of grazing or browsing animals; 4) prescribed fires; and 5) planting competitive native species and other land management practices (Grice, 2009).

Mitigation

Finally, when eradication, containment, and control are not options or have failed in managing the invasion of alien species, the last option is to "live with" this species in the best achievable way and mitigate its impacts on biodiversity and endangered species (Wittenberg et al., 2001). Mitigation is most commonly used in the conservation of endangered species and can be approached at various levels. Generally, mitigation means the translocation of a viable population of the endangered species to an ecosystem where the invasive species of concern does not occur or, in the case of a rehabilitated system, no longer occurs (NISC, 2001). However it should be noted that mitigation can be labor intensive and costly and is often seen as an intermediate measure to be taken together with eradication, containment or control for immediate efforts to rescue a critically endangered native species from extinction (Wittenberg et al., 2001)

Conclusion

Despite a number of strategies and action plans has been developed in order to prevent and control of invasive species, they have been still recognizing as one of the greatest threats to the ecological and economic well-being of the planet. This would be due to their nature of a wide range of distribution as well as successive adaptive strategy in new environment. Actually, human are the most important vectors for the distribution of these species, and thus it is important to differentiate between natural invasions and human introduction, whenever addressing the issue of alien species. Moreover, quarantine systems should be carried out together with public education and awareness programs. On the other hand, although a wide range of approaches, strategies, models, tools, and potential partners are available from international co-operation, the most relevant approach varies for each region as well as for each situation. Since invasions often are relevant to bio-geographical regions, and not just jurisdictional country boundaries, neighboring countries need to cooperate each other in order to control spread of these species. And also regional and global approaches towards prevention, management and control of these species need to be encouraged more intensively in the future.

References

CBD, (2010): Global Biodiversity Outlook 3 published by Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) (ISBN-92-9225-220-8) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/)

Clout N.M., Williams P.A. (eds.) (2009): Invasive Species Management: A Handbook of Principles and Techniques, Oxford University Press Inc., New York.

Dekker J., (2005): Biology and anthropology of plant invasions; Invasive Plants: Ecological and Agricultural Aspects, edited by Inderjit

Grice, T. (2009): Biosecurity and quarantine for preventing invasive species; Invasive Species Management: A Handbook of Principles and Techniques, edited by Clout, M. N. and Williams, P. A., Oxford University Press Inc., New York

GISP (2009): Global Invasive Species Programme - Annual Report, 1 January 2009 – 31 December 2009, published by GISP programme, United Nations Avenue, P.O. Box 633 – 00621, Nairob, Kenya

Inderjit et al. (eds.) (2005): Invasive Plants: Ecological and Agricultural Aspects, Published by Birkhäuser Verlag, P.O.Box 133, CH-4010 Basel, Switzerland

Maynard G. and Nowell D. (2009): Biosecurity and quarantine for preventing invasive species; Invasive Species Management: A Handbook of Principles and Techniques, edited by Clout, M. N. and Williams, P. A., Oxford University Press Inc., New York.

NISC, (2001): Meeting the Invasive Species Challenge: National Invasive Species Management Plan, Published by National Invasive Species Council (NISC) in 2001, Federal Government of United States of America, Downloaded from http://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/docs/council/mpfinal.pdf

Smith, R.D., Aradottir, G.I., Taylor, A. and Lyal, C. (2008): Invasive species management – what taxonomic support is needed?; Global Invasive Species Programme (GISP), Nairobi, Kenya

Stohlgren, T.J. and Jarnevich, C.S. (2009): Risk Assessment of Invasive Species, Invasive Species Management: A Handbook of Principles and Techniques, edited by Clout, M. N. and Williams, P. A., Oxford University Press Inc., New York

Wetzel G., (2005): Invasive plants: the process within wetland ecosystems; Invasive Plants: Ecological and Agricultural Aspects, edited by Inderjit

Wittenberg, R., Cock, J.W. (eds.) (2001): Invasive Alien Species: A Toolkit of Best Prevention and Management Practices. CAB International, Wallingford, Oxon, UK, xvii – 228

Worrall J. (2002): Review of systems for early detection and rapid response; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, Report for the National Invasive Species Council. Download available on http://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/toolkit/ detection.html

No comments:

Post a Comment